My goodness the weeks are passing by so quickly! During the fourth week, I watched my six new plates get colonized by a variety of settlers. The plates are fouling quickly, which is good because it means that a lot of organisms are settling down on it, but is also difficult because algae and particles have clouded the petri dish and make it hard to clearly see the organism in photos.

I decided to make a little side-experiment out of the redeployment. I actually deployed 12 plates with velcro on the sides instead of underneath. Of the 12 plates, six of them have abrasion on the top side (I scrubbed them with sandpaper to make the surface rough) while six of them are simply smooth plastic. I did this because supposedly settlers prefer to settle on roughened surfaces, and I figured that I could keep track of the rate of settlement on the clear plates versus the smooth plates. I'll count the number of settlers on each plates at some future time during the experiment and see whether the settlers really prefer rough over smooth.

For my main experiment, every day is the same procedure: get the petri dishes out of the water, look at each of them under the dissecting microscope, take photos of specific organisms, and keep track of new species that arrive on my plate. It sounds easy, but the entire process takes about 3-4 hours, and I do it every day (even the weekends). I am trying hard to be a good scientist, even if it means sacrificing my days off. On the bright side, once I start looking at the plates I'm often so absorbed in observing the changes that go on from day to day that the time goes by faster than it would otherwise.

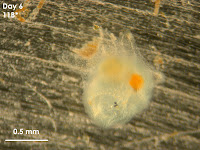

Here are some of the new organisms that have collected on my plates. I haven't had time to adjust the images or put in scale bars, but suffice to say that they are really tiny!

This is probably Schizoporella japonica, a bryozoan. Bryozoans are little animals that settle onto surfaces and reproduce asexually to form larger colonies. This kind of bryozoan is an encrusting bryozoan, meaning that it will continue to spread over the surface in a hard thin layer, like dried paint. When this bryozoan gets bigger, it will begin to reproduce assexually to form a colony.

This is probably Schizoporella japonica, a bryozoan. Bryozoans are little animals that settle onto surfaces and reproduce asexually to form larger colonies. This kind of bryozoan is an encrusting bryozoan, meaning that it will continue to spread over the surface in a hard thin layer, like dried paint. When this bryozoan gets bigger, it will begin to reproduce assexually to form a colony.

The spiral shell in this photo belongs to what I believe is a serpulid polychaete worm. You can see little feeding structures sticking out of the mouth of the shell. That is the worm. With these guys, I have to wait for them to peek out of their shells before photographing them.