In the eighth week, my adviser asked me to stay at OIMB for one extra week, in order to polish up the website. I happily agreed, so I'll be here for a total of nine weeks. The website definitely needs a good deal of work so I am happy to put in more hours on it. Though to be honest, photo processing is exhausting work!

Most of this week was spent preparing for final presentations, which took place on Friday. I spent most of Tuesday reviewing notes on good ways to structure presentations. I gave a few practice presentations to my friends and felt ready to present on Friday. The presentations took place in a classroom at the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology. Unfortunately the Hatfield Marine Science Center interns did not come down to Charleston for the day, but we did get the chance to see their presentations via Skype.

During my presentation, I spoke briefly about my future plans for the website (akiko-invertebrates.weebly.com), which I made to house the identification key which is my summer project. With my extra time at OIMB, I hope to label the basic anatomy of the juvenile settlers, and post a few photos of what each settler looks like as an adult colony. The website needs a lot of editing, and I have received many helpful comments about how to improve it. I hope that I have enough time to apply them all!

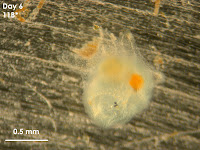

This is me looking through the dissecting microscope, which I used for the bulk of my work. Every day, for four weeks or so, I looked through this microscope to take pictures of the settling organisms.

A friend of mine took this photo of me and some ascidians. The large orange blobs are Distaplia occidentalis colonies, growing on a piece of netting that has been submerged for several months.